New Fiction Reviews:

Review by Lee Horsley

Steve Weddle’s The County Line (2024) is a big-hearted, wholly engrossing tale of thievery, betrayal and murder in the early years of the Great Depression. In the summer of 1933, Cottonmouth Tomlin returns home to a small town in southwest Arkansas just over the Louisiana border, after adventuring first to New Orleans and then to Central America. Leaving for Honduras, he’d had “a change of clothes and hope in the future. He’d come back with just a change of clothes. Better clothes, it was true, but not by much.”

Cottonmouth has returned for his uncle’s funeral, having been left an outlaw camp, “a scattering of cabins and an impassable road,” with a reputation for unsavoury goings-on. It is a useful place to hide kidnap victims or small-time outlaws on the run. As Cottonmouth gradually realises, however, his dilapidated camp is also a place that more powerful crooks might scheme to make their own. The County Line gives us a wonderful gallery of affectionately created ne’er-do-wells struggling to get by, hoping, after a drink or two, that they might, if luck is with them, knock over a bank with their four guns and seven bullets. Higher up the social scale, there are the formidably respectable but even more criminally inclined old sisters, Henrietta and Abigail Rudd – more than a match for any of the men in the town. And, eyeing the deficiencies of this local criminal hierarchy, there is the wholly untrustworthy interloper, Martello, who owns clubs in neighbouring Louisiana and “runs the whole corner of the state” – a man to both emulate and fear.

Caught between dangerous adversaries, Cottonmouth considers whether he could work with the well-heeled Martello, maybe welcome him as a guest and go over some ground rules with him: “That had been the plan, hadn’t it? Bring Martello in; bring in business.” But as he carries forward his underhanded schemes, Martello tells Cottonmouth, “Look around. This is my camp now. My men. Possession is nine-tenths of the law.” For Martello, it isn’t “about the history of the place” but about the future of a place he intends to shape and control. For Cottonmouth, on the other hand, it is home. There is continuity and a sense of belonging imparted by land his family has owned for nearly a hundred years: “I’ll take family and community over Hessian soldiers any day”.

The County Line is a lively, humorous and above all compassionate story of lives worn down by the grinding years of the Great Depression, and of the choices forced by desperation. As Cottonmouth ponders his direction in life, he reflects, “Head back home from Honduras, and the next thing you know, you’re running a kidnapping ring out of your family’s hunting camp. What a world, he thought. What a world. —“

Isabelle Kenyon, The Dark Within Them (2024)

Review by Kate Horsley

Isabelle Kenyon’s debut novel, The Dark Within Them, is a beautifully written and intricately plotted literary mystery. Set in Lehi, a safe Mormon town in Utah County, where Amber settles with her new husband, Chad, and two children, Gilly and Ivan, Kenyon’s book explores themes of faith, motherhood and marriage with nuance. At the same time, the plot propels the reader forward with the claustrophobic tension of recent grip-lit classics like The Girl on the Train.

Following on the death of her husband, Amber works the faith-healing circuit, where she has found fame and following, making a name for herself as an independent force to be reckoned with. But, as we come to discover, Amber’s life won’t allow for complete independence: “There were only certain circles of the church open to single mothers. And most of them sought to patch the vacancy in your life for you. It was difficult to gain influence or an audience for her work as a visionary, as an unattached female. Folks around these parts attached derogatory terms to her. There was a sense of distrust, like the fear of witches concocting spells against the town.”

Chad, a practising Mormon, apparent good guy, and Amber super-fan, fantasizes about Amber being his trophy wife. Amber, meanwhile, dreams that Chad will provide her children with a secure home and father figure and Amber herself with conventional credibility: “A husband seemed to ground that fear, presented her as a caregiver, a sandwich-maker, the giver of cupcakes.” But the course of not-especially-true love never did run smooth.

One of my favourite things about The Dark Within Them is the moral ambiguity of the two main characters. Charismatic Amber flirts and charms her way through the book’s first chapters like a classic femme fatale, a question mark hovering tantalisingly over the circumstances of her abusive husband’s death. Compared to Amber, love interest Chad seems clumsy and insecure, often out of his depth: “He felt a little sick. Like an uncool dad about to surf his way through an Ariana Grande concert.”

Hypnotic Amber, meanwhile, hides a bruised strength under her brittle exterior: “Amber’s smile stretched and broke like cracked PVA glue.” All the while, the sultry landscape lurks around them, described in lush and unsettling detail, which was another of my favourite aspects of this richly layered book: “There were mosquitoes lovingly kissing scarf-less necks, liberal in their affections, and a rustling in the hedges, which Chad suspected might be crickets.” Elsewhere, dubious characters merge with the landscape like chameleons taking on protective colouration: “A ruddy smear of a man. He stood in front of a huge house-much too big for one man living alone—of brown brick, the colour of soil. It blended into the arid farmland behind him.” In the half-light of this noir setting, Chad seems a moth lured towards the bright light of Amber’s spirituality.

As the plot unfurls, though, their relationship takes a series of break-neck twists and turns, causing the reader to question if Chad is at who he first seemed or something much more dangerous. When Amber’s daughter Gilly dies suddenly and under strange circumstances, Amber confronts a tight knot of secrecy in the Lehi community, who will do anything to protect their own. As she fights to find answers and a way out, she discovers that nothing in Lehi is as it seems.

Isabelle Kenyon is a Manchester writer and the author of 5 chapbooks including Growing Pains (Indigo Dreams). She has had work and articles published internationally and newspapers such as The Somerville Times and The Bookseller.

With its morally culpable characters and mysterious setting, Kenyon’s journey through faith and betrayal keeps its readers constantly guessing. We highly recommend this stylish and gripping debut!

Karen Taylor, Dark Arts (2023)

Review by Kate Horsley

Karen Taylor’s Dark Arts is a page-turning mystery, combining well-crafted characterisation with a lively plot. The prequel to her debut, Fairest Creatures, it sees “grieving artist Rachel Matthews return home to Penzance in the winter of 2018, to find herself at the centre of a series of crimes connected to the Cornish arts community. DI Brandon Hammett, a Texan with Cornish roots, is leading the investigation. Dark Arts features many of the same characters as Fairest Creatures and provides further insights and intrigues into the rich cast of players.”

In the names of some of its characters, including series detective, DI Brandon Hammett, this novel gives sly nods to the traditions of classic detection and film noir, playing with the familiar ingredients of the cosy mystery – intrigue, suspense, romance and murder – but Taylor adds a humour and freshness that’s all her own.

One of the real strengths of this gripping book is the way the Cornish setting is evoked, not just as a backdrop for the action, but as an affectionately drawn character:

“She looked past him towards St Michael’s Mount in the east. The medieval fortress was drenched in blood-red light. An hour earlier it had been dark as a shadow, rising from the water like some mythical seabird. To the west was the hilly fishing town of Newlyn, its white brick houses stacked like cartons of fudge.”

The novel opens with evocations of the Solstice Montol festival in Penzance, showing us “lines of masked revellers and musicians. Dickensian figures in dark cloaks and top hats lined the pavements.” Into this colourful and chaotic scene is thrust main character, Rachel Matthews – daughter of painters Lawrence and Lizzie Matthews and an artist herself. Rachel’s grief over the loss of her young son, Oliver, is poignantly evoked and this, along with an encounter with a lost love, drives much of her – often emotionally intense and heartfelt – plot arc. Equally well drawn is Rachel’s tender and sometimes anxious relationship with her eccentric mother, Lizzie, whose affliction with ‘happy dementia’ is handled delicately. Like the Cornish setting, the novel’s art world milieu adds rich detail to the story:

“Rachel braced herself as she followed her mother into the studio. This room, at least, hadn’t changed one bit since Lawrence ascended to the great garret in the sky. The smell of turps and oils, the half-filled paint pots with their congealed lids, the massive old wooden table which ran the length of the room, covered in smears and spills, was as it should be. As it always was.”

Taylor interweaves Rachel’s narration with that of series protagonist, DI Brandon Hammett, who must delve into a shadowy world of art dealing and drug smuggling to solve a series of deaths. Rachel’s arrival in Penzance coincides with the first of these crimes – but is she involved, responsible even? She proves to be a bold and resourceful investigator, someone who Brandon can confide in. Both Rachel and Brandon “seek recovery and purpose. Rachel uses work at a local school to help her heal. Recently widowed, Brandon looks to set the world to rights and protect his hometown. A town under attack. Violent county lines drugs runners compete with local dealers and smugglers, and the Penzance arts community is rocked to the core.”

Karen Taylor is a UEA alumni crime writer whose latest novel Fairest Creatures was longlisted for the 2020 Crime Writers’ Association Debut Dagger. Born in London, Karen is also a journalist and editor with wide ranging experience, covering anything from business to lifestyle. She divides her time between Penzance and London.

Dark Arts is a mystery that keeps the reader gripped to the very end. For any of our readers who haven’t yet enjoyed this or Fairest Creatures, we highly recommend the whole series.

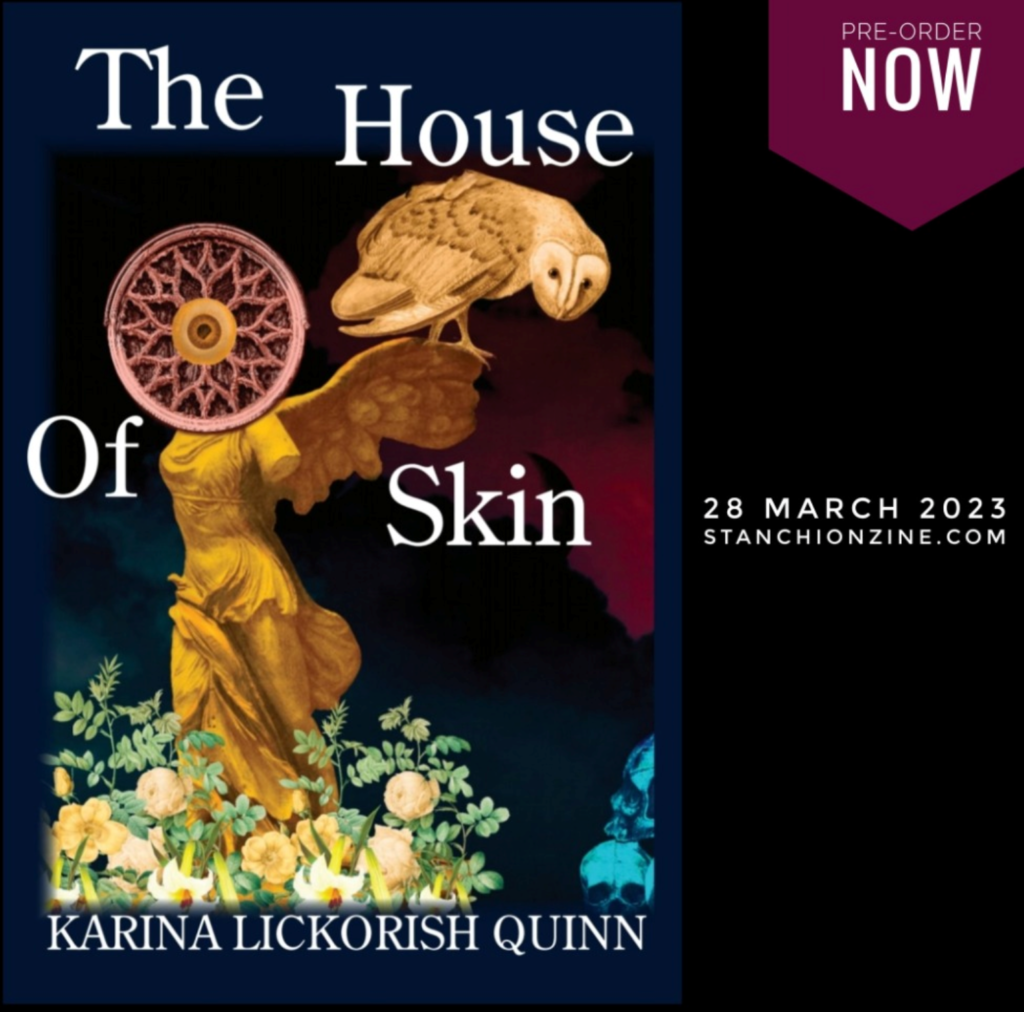

Karina Lickorish Quinn, The House of Skin (2023)

Reviewed by Kate Horsley

This week I was lucky enough to get my hands on an advanced copy of The House of Skin, a literary surrealist horror/thriller novelette by the wildly talented Karina Lickorish Quinn, published by Stanchion. I finished it in a single thrilling sitting and had some quite amazing nightmares afterwards!

The House of Skin is a tale of a house suffused with dread, inside which shift the unsettling friendships of a mysterious art world clique. Breathtakingly inventive, this novelette fuses the compulsive suspense of a Gothic page-turner with artfully wrought, sensuous prose. Karina Lickorish Quinn’s writing bristles with wit whilst burrowing knowingly under the reader’s skin. This sophisticated thriller is the very thing it dissects, a work of art that will seduce and stun you, and one that you won’t soon forget!

From the publisher

Synopsis: At a gallery one night, a young sculptor meets Cyan, an art collector with a turquoise beard, a detached charm, and a wife recently dead. Bewitched by him and his posse of elegant friends, the sculptor agrees to accompany them to a party and finds herself plunged into their world of eccentric decadence. Cyan and his clique are worshipped by flocks of struggling artists, all desperate to be discovered. When Cyan invites her to complete a residency at his mansion home, the sculptor believes her big break has finally come. But what is it about the house that so unnerves her? And how much will she sacrifice for success?

You can buy advanced copies to ship in late March 2023 here: https://www.stanchionzine.com/product-page/the-house-of-skin

The House of Skin is perfect for fans of Carmen Maria Machado and Clarice Lispector.

Karina Lickorish Quinn is a Peruvian-British writer whose first novel The Dust Never Settles was published by Oneworld in the UK and Commonwealth in 2021. The Spanish translation, El Polvo Nunca Se Asienta (Arde, 2022), was chosen as a summer must-read by the national Spanish TV channel La Sexta. She has been hailed by Antonio Iturbe in La Vanguardia as a ‘powerful literary voice full of echoes’. Her short stories have been published in The White Review online, Asymptote, Wasafiri , Palabritas, The Journal of Latina Critical Feminism and in Un Nuevo Sol, the first anthology of British-Latinx writing. Karina Lickorish Quinn is a lecturer in Creative Writing at Royal Holloway University of London.

Nancy Tucker, The First Day of Spring (2022)

Reviewed by Lee Horsley

Nancy Tucker’s The First Day of Spring is the compelling, forcefully written story of a child murderer. The shock of the first sentence – “I killed a little boy today” – takes us with great immediacy into the mind and grim life of Chrissie. Eight years old, Chrissie is socially ostracized, lonely and appallingly treated by a mother who rejects and ignores her, dragging her along on one humiliating occasion to an adoption agency in the hope that she can simply give her away. Clever and resourceful, Chrissie is able to use her abilities only to try to find small survival strategies and to get someone – anyone – to notice her.

Tucker has the courage to risk the slow, repetitive accumulation of detail in the child’s narrative – tense and moving for us as readers, but also capturing the sense of inescapable daily repetition, the countless deprivations in the life of a child who has nothing. She is wretchedly alone in her small world of ‘the streets’, in which everyone tries as far as possible to ignore her. Her only goal is often to gain entry to a house where the parents will feel compelled to offer her a little food. Facing slow starvation, she is frequently unable to think of anything other than her hunger. At home, “the kitchen cupboards had nothing inside except sugar and moths”.

For a brief time, the act of killing another child gives Chrissie a feeling of specialness. When people around her talk about the murder of the boy she repeatedly tries to hint at her secret, and the knowledge of her guilt gives her a fizzing sense of power: “I could feel everyone’s eyes on my back, and I bubbled with the power of it.”

Chrissie’s narrative alternates with that of Julia, the name that grown-up Chrissie takes. We follow her after her release from the secure unit in which she has spent the intervening years. Now herself a parent, Julia not only carries the burden of her childhood guilt but is despairingly trying to learn how to mother her four-year old daughter Molly, terrified at every turn that she is doomed to fail and that, everywhere she goes, there are “scheming social workers crouched in the shadows, waiting to wrench her out of my useless hands”.

People who were around in the 1960s and 1970s may well remember press accounts of the girl who strangled two small boys when she was 10 or 11, and may also be familiar with the biographer Gitta Sereny’s The Case of Mary Bell (1972). Sereny also wrote a second book, based on extensive interviews with Bell in later life, called Cries Unheard (1998). But although one assumes that these historical accounts influenced Tucker’s work, her novel stands entirely on its own. The cumulative effect of The First Day of Spring is the creation of an unforgettably poignant and disturbing narrative voice. There is no romanticised poverty here. Instead, there is the overwhelming accumulation of inner torments – the harrowing substance of a life of desperation.

Simon Van der Velde, The Silent Brother (2022)

Reviewed by Lee Horsley

Simon Van der Velde’s The Silent Brother is a powerfully written, deeply affecting coming of age story. It is dark, harrowing and often brutally, bone-crunchingly violent, but also throughout conveys the urgent need for loving bonds – none more important than that between Tommy Farrier and his younger brother Benjy.

When we first meet Tommy, he’s five years old, living with his little brother, his alcoholic mam and Daryl, his vicious step-dad. This first section of the novel gives us an intensely realised picture of the frightening, near-intolerable life of the young brothers, trying to cling on to one another and to the few things that give their lives meaning. When the social services step in to remove the boys from their abusive home, their mam makes them hide. In a heart-stopping scene, jammed together at the back of a large cupboard, they try desperately to be quiet:

“… he clings to the neck of my jarmas cos he knows…I want him to stay. So I can hold him. So his fear can make me stronger. He knows that I’m only a coward pretending to be brave and that I need him, like always. So he stays. Even when the voices are booming just outside…”

Though the terrified Benjy remains completely silent, Tommy himself inadvertently makes a sound that leads the authorities to their hiding place. It is Benjy rather than him who is discovered and dragged away, leaving Tommy tortured by acute guilt throughout the novel. The family, changing their name to Boyle, moves to Newcastle to evade the attentions of the social workers: “The van stops and we’re there, where The Social won’t find us, and I’m Tommy Boyle, age five-and-a-half, and I don’t have a brother and I never did.” Even Daryl’s worst threats, however, can’t erase Benjy’s reality, and through all of the brutality of his later years, Tommy holds fiercely to the reality of his deep, wordless bond with Benjy.

In the second part of the novel, a teenage Tommy struggles to find ways of surviving both at home and in the streets. Daryl’s violence destroys what’s left of Tommy’s boyhood world: the “magic power” that his mam once seemed to have is beaten out of her, and “Now I understand that’s how real life works.” On the streets, life only seems workable if he accepts what’s on offer: when he’s fifteen, Maxi hands him two plastic money bags bulging with home-grown skunk and he sets off to make the deals that might at least give him a way out of his abusive home. Chosen as much as anything for his “innocent face”, Tommy convinces himself he has the world’s easiest job: “a hundred quid a night for sitting in a posh bar and having a pint.” Will his choice define him for his whole life or is there is any possibility of escape from a criminal world that consists entirely of treachery and savagery, “the booze and the drugs, the dodgy deals and stolen money”? Is it possible to “change where you’re going” and maybe even, if you do, to “change who you are”?

The Silent Brother creates a narrative that brings readers painfully close to Tommy’s struggle. We’re compelled throughout by his sense of failing all of those closest to him, by the omnipresent threat of violence and the occasional glimmer of redemptive possibilities. Even recognising that he was “always screwed” from the moment he chose his path, he searches for a hidden inner strength that might be reclaimed. As he drives on to face his adversaries, he thinks back, “trying to get in touch with little Tommy Boyle. Not with the guilt and the blame, but with the fight. The kid that made Daryl break his finger before he’d say he didn’t have a brother.”

M. W. Craven, The Botanist (2022)

Reviewed by Lee Horsley

M.W. Craven’s The Botanist is a tense, gripping mystery, combining strong characterisation with intricate plotting. The novel plays with familiar ingredients of the classic detective story – locked rooms, mysterious poisons – but Craven brings them together with both originality and dexterity. For a start, he offers us not one but two locked room mysteries:

“We have a killer in London who warns his victims yet still gets to them, and up north someone murdered Estelle Doyle’s father and walked away from the crime scene without treading on a single fucking snowflake.”

Although the challenges set by the puzzle of death in locked rooms and by the machinations of the novel’s methodical poisoner draw on traditional devices, the plot is very much intertwined with contemporary preoccupations. Those targeted by the killer include, for example, a Pharma Bro who uses corrupt commercial practices to buy up the rights to essential medicines and media celebrities with appalling views on women and immigrants. The public face of the poisoner’s scheme is integrally related to the modern media world, within which toxic personalities can flourish, disseminating their poisonous views and profiting from others’ weakness.

The mystery is permeated by Gothic darkness, with a killer so devious and skilled that it seems impossible to protect his victims, in spite of the fact that he forewarns them of their doom. Their murders are imagined in macabre detail, as poisons insidiously invade internal organs, bringing grotesque deaths however securely the chosen victims have tried to hide themselves.

The Botanist is the fifth novel in Craven’s hugely successful Washington Poe series, which began in 2018 with The Puppet Show, and part of our engagement with the narrative is to do with the fact that the central characters in Poe’s life are not immune from the danger. Like the earlier books, The Botanist appeals to us by a wonderful combination of gruesome crime plots with the warmth and affectionate humour of Detective Sergeant Poe’s friendships with his “dream team”. The most important relationship in the series is between the abrasive, uncompromising Poe and the sweetly guileless genius Tilly Bradshaw, a civilian analyst whose technical wizardry becomes indispensable to every investigation. But the team as a whole is integral to both the appeal and the suspense of the series:

“Anyone who knows how to read behind the headlines will know who you prefer to work with. Tilly’s Mole People, as you call them, Superintendent Nightingale—’ ‘And Estelle Doyle,’ Poe finished for her. ‘What if someone wanted to mess with the dream team. To borrow a saying from my baseball-crazy father: what if someone wanted to bench one of your star players?’”

It’s a ‘what if’ that keeps us hooked to the very end. For any of our readers who haven’t yet enjoyed Craven’s Poe and Tilly novels, we highly recommend the whole series.

See more of Crimeculture’s recent reviews below:

Gilly Macmillan, The Long Weekend

Gilly Macmillan’s The Long Weekend is a riveting novel – complex, dark and disturbing. Close friends have planned an idyllic weekend away in a remote, beautiful Northumbrian retreat. But their long weekend, it turns out, is also a ‘lost’ weekend. The landscape itself becomes impenetrably dark and dangerous as a storm approaches. Read our review of The Long Weekend.

Rachel Howzell Hall, These Toxic Things

Rachel Howzell Hall’s new stand-alone, These Toxic Things, is a suspenseful, energetic and inventive novel. The protagonist, Mickie Lambert, is lively and intelligent – but also young and vulnerable. At the beginning of the novel, Mickie is embarking on a new project in her role as a digtital archaeologist. Read our Review of These Toxic Things.

Lucy Foley, The Paris Apartment

Lucy Foley’s The Paris Apartment is a cleverly constructed mystery, immersive and consistently suspenseful. At its centre is an elegant Parisian apartment block, Number Twelve Rue des Amants – an aging building of many locked rooms, sinister passageways and suspiciously watchful eyes. Long-held secrets are sequestered in every corner of the building. Read our review of The Paris Apartment.

Will Dean, The Last Thing to Burn

Reading Will Dean’s The Last Thing to Burn (2021) is an intense, claustrophobic, visceral and terrifying experience. Thanh Dao, Dean’s narrator, came with her sister to the UK, deceived by the false promise of jobs. Now she despairs of ever escaping from the cruel and implacable Lenn, who has imprisoned her on his remote pig farm for the last seven years. Read our review of The Last Thing to Burn.

Sarah Penner, The Lost Apothecary

In her debut novel, The Lost Apothecary (2021), Sarah Penner imagines an intriguing and suspenseful intersection between the eighteenth and twenty-first centuries. In 1791, we follow the murderous life of a late eighteenth-century apothecary; in our own time, we’re immersed in the historical investigations of a young woman who stumbles on a clue that kindles an overwhelming desire to understand the life of the mysterious apothecary. Read our review of The Lost Apothecary.

William Boyle, Shoot the Moonlight Out

William Boyle is wonderfully skilled in creating vivid, memorable characters. In Shoot the Moonlight Out (2021), as in his earlier novels, he draws us into the encounters – whether quirky friendships, unexpected love or ill-conceived criminal transgressions – that upend the lives of those inhabiting their small corner of Brooklyn. Read our review of Shoot the Moonlight Out.

Melanie Golding, The Replacement

Part psychological thriller, part police procedural and part dark fairy tale, The Replacement (2021) continues the police procedural framework of Golding’s debut novel, the hugely successful Little Darlings (2020), and similarly draws on powerful folk myths… Golding’s central protagonist is the strong-willed, intuitive DS Joanna Harper, whose own life has been shaped by the disturbing fluidity of human relationships. Read our review of The Replacement.

Liz Nugent, Our Little Cruelties

In Our Little Cruelties (2020), Liz Nugent again demonstrates her extraordinary ability to bring to life characters who both repel and fascinate us. One of the most darkly noir of contemporary crime writers, she excels in the creation of tense, gripping dramas about people imprisoned in their own obsessions and their catastrophic errors of judgement. Read our review of Our Little Cruelties.

Richard Osman, The Man Who Died Twice

Richard Osman’s The Man Who Died Twice (2021) is an ebullient and superbly entertaining take on the Golden Age detective novel.This is the second book in his ‘Thursday Murder Club’ series, which inventively updates the formula of country village atmosphere and loveable, eccentric characters. Read our review of The Man Who Died Twice.

Lisa Jewell, The Night She Disappeared

Lisa Jewell’s The Night She Disappeared draws us in with an absorbing, beautifully crafted story that holds us in suspense throughout. As in Jewell’s other novels, our attention is compelled not only by the intricate plotting but by characters so richly created and memorable that they stay in the reader’s mind long after the final pages. Read our review of The Night She Disappeared.

Megan Abbott, The Turnout

Megan Abbott’s The Turnout is a mesmerising novel, wonderfully written and vividly imagined. At once brutal and delicate, it takes place in the world of a decaying, secret-laden ballet school. Some of Abbott’s most remarkable earlier crime novels have also explored, to stunning effect, the obsessive, competitive lives of teenage girls who commit themselves to intensely demanding physical disciplines – the cheerleaders of Dare Me, the gymnasts of You Will Know Me. Read our review of The Turnout.

Aaron Philip Clark, Under Color of Law

Aaron Philip Clark’s Under Color of Law is a gripping, sharply observed, fast-moving journey through the dark and treacherous world of the LAPD. It is written as the first-person, present tense narrative of Detective Trevor ‘Finn’ Finnegan, a young black cop who daily confronts the kind of horrors “that strip a person bare and leave them hollow”. Read our review of Under Color of Law.

Stuart Neville, The House of Ashes (2021)

The House of Ashes is a stunning novel, brutal, disturbing and completely riveting. It’s a crime novel but also a deeply affecting ghost story, the ghosts of children appearing to those who can see them, shadowy witnesses to the violence suffered: “A deeper darkness took her for some time, her slumber haunted by broken dreams of broken children between walls and beneath floors…” Read our review of The House of Ashes.

Catriona Ward, The Last House on Needless Street (2021)

Catriona Ward’s The Last House on Needless Street is a surreal and fascinating novel. In the opening chapters, it would seem to be about a serial killer, Ted Bannerman, hunted by Dee, a young woman who is convinced he killed her sister when she was six. Ted has locked himself away in a run down, sinister place on the edge of a forest, where memories “lie around the house, in drifts as deep as snow.” Ward’s novel very skilfully creates a dark mixture of child murder and gothic horror, drawing us into a world that is haunted, disturbing and disorienting. Read our review of The Last House on Needless Street.

Caitlin Mullen, Please See Us (2021)

Mullen’s protagonists, Lily and Clara, are very unlike one another, but both struggling to build new lives for themselves. They are brought together under the extreme pressure of violent events, desperate to work out what has been happening and terrified that they may themselves become victims. Lily reflects, “I was so tired of being afraid. And yet, it seemed that was all this summer was: learning all of the ways that dread could creep into my days.” Read our review of Please See Us.

Inga Vesper, The Long Long Afternoon (2021)

Inga Vesper’s The Long Long Afternoon is a beautifully atmospheric and wholly absorbing crime novel, set in 1950s Santa Monica. Vesper’s title conjures up the placid, unbroken calm of a Californian idyll – a sun-drenched suburban life, where affluent housewives display their domestic accomplishments, their blue pools, their May-green lawns. But – as any reader of Chandler will suspect – we will inevitably discover that underneath this claustrophobic, carefully constructed surface there are hidden lies, transgressions and bloodstains on the kitchen floor. Read our review of The Long Long Afternoon.

Jessica Barry, Don’t Turn Around, 2021

“Wasn’t living under the constant threat of danger just a part of being a woman in this world?” Jessica Barry’s Don’t Turn Around is a gripping, swiftly paced female road novel. Her evocative prose propels us into the lives of two strong, determined women, thrown together on a nightmarish journey, facing dangers that neither of them anticipated. Read our review of Don’t Turn Around.

Throughout 2020, Crimeculture reviewed a selection of the outstanding crime novels we enjoyed during the lockdown.

Crimeculture’s Lockdown Favourites

Jane Harper, The Survivors, 2020

Jane Harper’s The Survivors is an engrossing, suspenseful novel, with strong characters and an intensely realised landscape. It takes place in the tiny, isolated Tasmanian town of Evelyn Bay, sparsely populated except during the tourist season, when holidaymakers outnumber the town’s inhabitants.

Read our review of The Survivors

Agnes Ravatn, The Seven Doors, 2020

Agnes Ravatn’s psychological thriller, The Seven Doors, is a haunting and disturbing exploration of guilt and deception – and of an obstinate determination to expose hidden truths. Ravatn’s subtle, mesmerizing prose draws us into a complex skein of family secrets.

Read our review of The Seven Doors…

Hannelore Cayre, The Godmother (2019)

Hannelore Cayre’s The Godmother (published as La Daronne in France) was one of the unexpected delights of this year’s reading. It began to receive widespread recognition when Cayre – a criminal lawyer as well as a screenwriter and director – won both the European Crime Fiction Prizeand the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, France’s most prestigious award for crime fiction. Read our review of The Godmother…

Read reviews of more of our Lockdown Favourites:

Camilla Läckberg, The Golden Cage

Louise Candlish, The Other Passenger

Dreda Say Mitchell, Spare Room

Thomas Mullen, Midnight Atlanta

Rone Tempest, The Last Western

William Boyle, A Friend is a Gift You Give Yourself

Michael Farris Smith, Blackwood

Oyinkan Braithwaite, My Sister, the Serial Killer

S. A. Cosby, Blacktop Wasteland