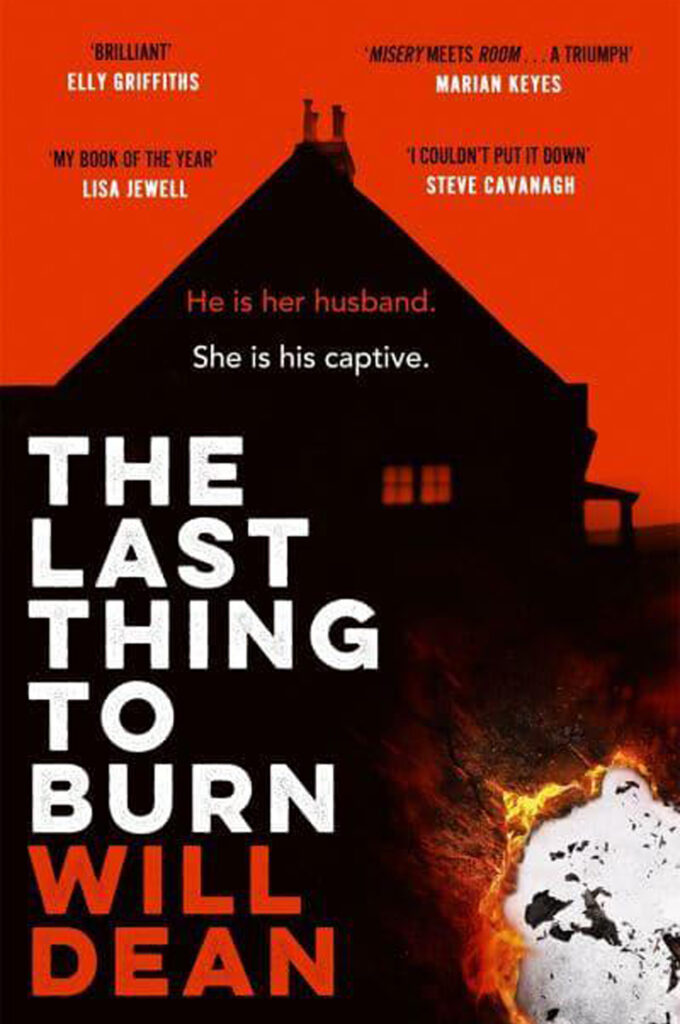

Will Dean, The Last Thing to Burn (2021)

Reviewed by Lee Horsley

Reading Will Dean’s The Last Thing to Burn is an intense, claustrophobic, visceral and terrifying experience. Thanh Dao, Dean’s narrator, came with her sister to the UK, deceived by the false promise of jobs. Now she despairs of ever escaping from the cruel and implacable Lenn, who has imprisoned her on his remote pig farm for the last seven years.

The horror of the story is most powerfully conveyed through mundane everyday details. At the heart of the horror is a monster is who thinks his grotesque parody of family life is a form of cosy domesticity. It is his way of establishing normality as he knows it. Thanh Dao is harshly schooled over the years to prepare dinner exactly as his mother had done – the dry chicken, over-cooked sprouts, mashed potatoes with Oxo, followed by unlocking the television cabinet so they can watch Match of the Day:

“He sits back down on his armchair and I sit the way he likes me to sit, on the floor by his knees. By his feet… ‘It’s all right, ain’t it, this life?’ He sips his beige tea, and the fire from the stove lights one side of his face. ‘We’re warm, under decent roof, full bellies, together, not all bad, is it?’”

Any woman who belongs to Lenn is given his mother’s name. Thanh Dao’s inner refrain of “My name is not Jane” repeatedly underscores the nature of her captivity, the removal of all that originally constituted her individuality. He methodically destroys her identity, object by object. When she disobeys one of his many rules, he not only brutally assaults her but takes from her and burns one more of the seventeen items (ID card, family photos, letters from her sister…) that she was clinging to as reminders of her real self.

The site of Thanh’s imprisonment is a bleak, run-down farmhouse in eastern England’s Fenlands, from which she can see, all around her, only miles of nothingness. Within the house, she is surveilled by seven cameras, creating tapes that Lenn reviews daily on his computer, watching for any deviations from established routines. Escape is impossible. The flat, featureless landscape of the fens facilitates constant observation. Wherever he is on the farm, Lenn can see his house. Should she try to sneak away, in any direction, she knows that he will immediately return to punish her transgression:

“I live in an open prison surrounded by wall-less fields and fence-less fens. It’s the vastness of these flatlands that keeps me prisoner here. I am contained; incarcerated in the most open landscape of them all.”

Dean only allows us the briefest glimpses of possible escape routes, and The Last Thing to Burn holds grim despair and slender possibility in balance until the end. As horrifying details accumulate, we are compelled to read on both by the haunting power of Thanh’s narrative and by our mounting anxiety about whether escape is even remotely possible from the “hideous purgatory” of her life.