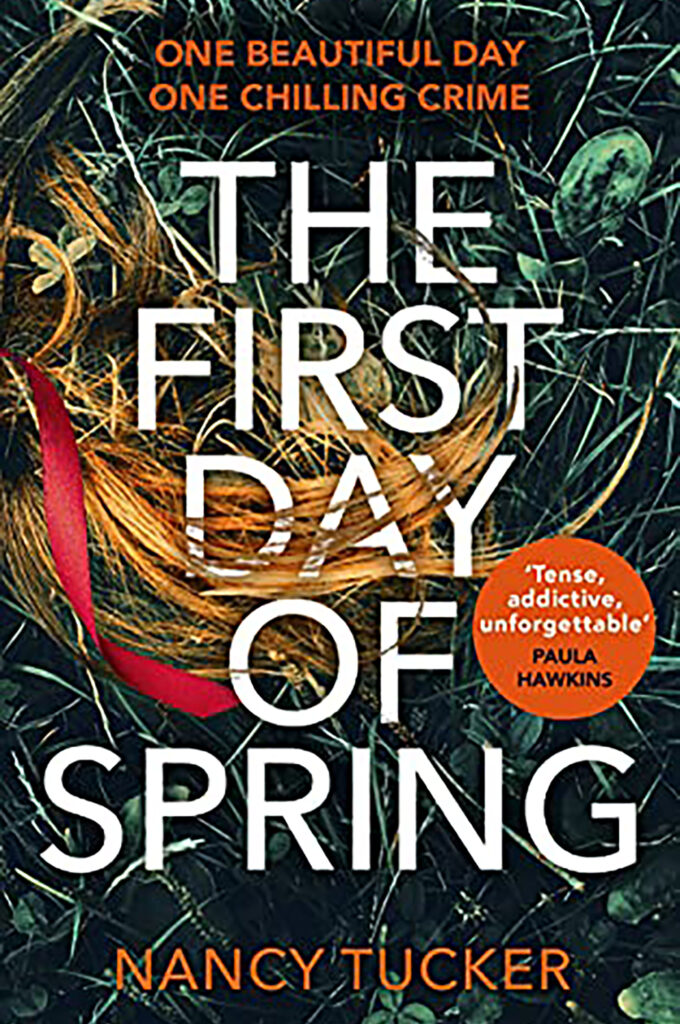

Nancy Tucker, The First Day of Spring (2022)

Reviewed by Lee Horsley

Nancy Tucker’s The First Day of Spring is the compelling, forcefully written story of a child murderer. The shock of the first sentence – “I killed a little boy today” – takes us with great immediacy into the mind and grim life of Chrissie. Eight years old, Chrissie is socially ostracized, lonely and appallingly treated by a mother who rejects and ignores her, dragging her along on one humiliating occasion to an adoption agency in the hope that she can simply give her away. Clever and resourceful, Chrissie is able to use her abilities only to try to find small survival strategies and to get someone – anyone – to notice her.

Tucker has the courage to risk the slow, repetitive accumulation of detail in the child’s narrative – tense and moving for us as readers, but also capturing the sense of inescapable daily repetition, the countless deprivations in the life of a child who has nothing. She is wretchedly alone in her small world of ‘the streets’, in which everyone tries as far as possible to ignore her. Her only goal is often to gain entry to a house where the parents will feel compelled to offer her a little food. Facing slow starvation, she is frequently unable to think of anything other than her hunger. At home, “the kitchen cupboards had nothing inside except sugar and moths”.

For a brief time, the act of killing another child gives Chrissie a feeling of specialness. When people around her talk about the murder of the boy she repeatedly tries to hint at her secret, and the knowledge of her guilt gives her a fizzing sense of power: “I could feel everyone’s eyes on my back, and I bubbled with the power of it.”

Chrissie’s narrative alternates with that of Julia, the name that grown-up Chrissie takes. We follow her after her release from the secure unit in which she has spent the intervening years. Now herself a parent, Julia not only carries the burden of her childhood guilt but is despairingly trying to learn how to mother her four-year old daughter Molly, terrified at every turn that she is doomed to fail and that, everywhere she goes, there are “scheming social workers crouched in the shadows, waiting to wrench her out of my useless hands”.

People who were around in the 1960s and 1970s may well remember press accounts of the girl who strangled two small boys when she was 10 or 11, and may also be familiar with the biographer Gitta Sereny’s The Case of Mary Bell (1972). Sereny also wrote a second book, based on extensive interviews with Bell in later life, called Cries Unheard (1998). But although one assumes that these historical accounts influenced Tucker’s work, her novel stands entirely on its own. The cumulative effect of The First Day of Spring is the creation of an unforgettably poignant and disturbing narrative voice. There is no romanticised poverty here. Instead, there is the overwhelming accumulation of inner torments – the harrowing substance of a life of desperation.