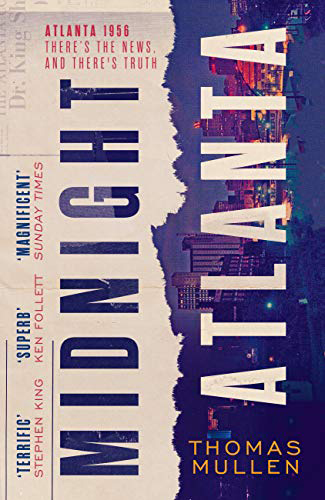

Thomas Mullen,Midnight Atlanta (July 2020)

Review by Lee Horsley

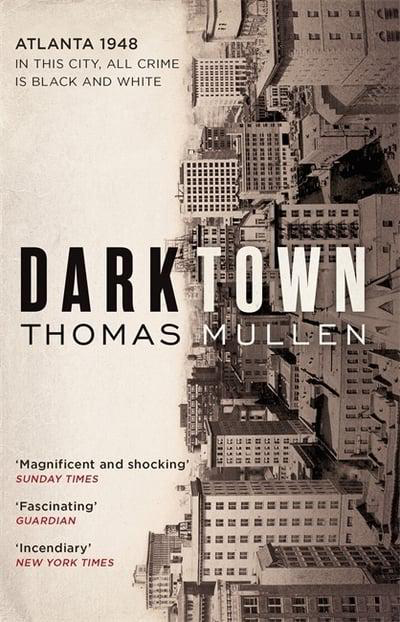

Thomas Mullen’s Midnight Atlanta is a compelling sequel to Darktown (2017) and Lightning Men (2018). Like the earlier novels, it achieves a remarkable blend of strong characters, an intriguing mystery and fascinating historical insights into the violent, disturbing terrain of post-World War II Atlanta. It is a period when those seeking change are pushing against entrenched privilege and prejudice, and Mullen’s well-researched narrative lays bare the grim realities of this world – its racism, moneyed power, official corruption, miscarriages of justice and police brutality.

Midnight Atlanta carries the historical narrative forward into the time when Martin Luther King Jr, a native of Atlanta, was emerging to galvanize civil rights activism; in the bordering state of Alabama, the Montgomery bus boycott was taking place; the unanimous Supreme Court verdict in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka had been handed down in May 1954. The challenges to Southern segregation were mounting, and the violence and prejudice endured by Mullen’s characters are inseparable from this wider struggle.

The two black cops introduced in Darktown remain central protagonists. Lucius Boggs is still a part of the city’s first black police force, and his ex-partner, Tommy Smith, is now a crime reporter for the Atlanta Daily Times, the only black daily in America. They have on their side Joe McInnis, the one white cop who serves in the black precinct, a man increasingly viewed by the white community “as a traitor working behind enemy lines.”

The plot centres on their efforts to solve the murder of Smith’s own black newspaper editor, Arthur Bishop, who is killed whilst working alone in his office, reviewing his notes from a research trip to Montgomery. Tommy Smith, who is also working late and who finds the dying Bishop, must struggle to clear his name, and the hunt for Bishop’s killer is made all the more urgent by the fact that his innocent wife has been arrested for his murder by police anxious to bring the case to a speedy conclusion. Smith, Boggs and McInnis, each pursuing his own lines of enquiry, have to contend not only with interfering federal agents but with corrupt cops who take violent issue with their investigations.

Throughout Midnight Atlanta, Mullen gives his readers deeply disturbing insights into the damage being inflicted on black lives and also into the entrenched resistance to removing barriers to prejudice. As the conflict deepens, McInnis reflects that “It was the panic over Brown and its specter of government-imposed integration, the retreat to opposing bunkers, the growing fear that anything less than hostility to Negroes would imperil the Southern way of life.” His commitment to his own work with the black cops grows as he recognises the hardening of white prejudice in the wake of the Brown decision:

“Now people saw him as helping colored folk at a time when they were already emboldened and trying to take what did not belong to them. In every other white person’s eyes, McInnis was working for the wrong side, giving his aid and comfort to an existential threat.”

Mullen engages and challenges his readers throughout. Midnight Atlanta is both a gripping historical mystery story and a novel that urgently addresses the anger and prejudice surrounding contemporary racial violence.